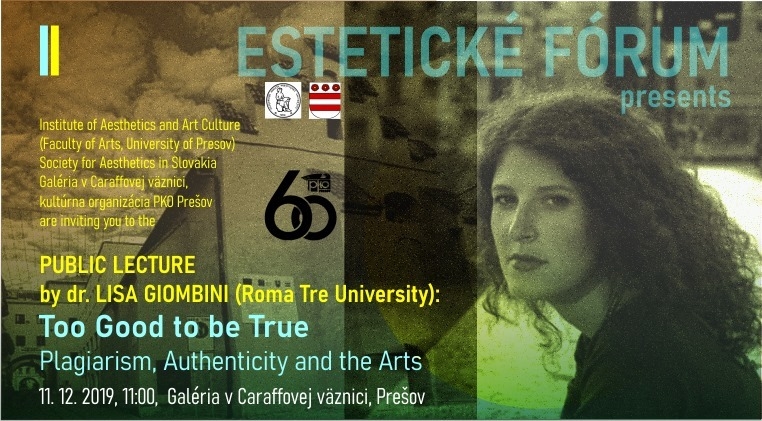

Estetické fórum: Too Good to be True. Plagiarism, Authenticity and the Arts

Z prednášky bol vyhotovený videozáznam, ktorý je dostupný na webstránke Inštitútu estetiky a umeleckej kultúry FF PU a Spoločnosti pre estetiku na Slovensku.

Dr. Lisa Giombini: Too Good to be True. Plagiarism, Authenticity and the Arts

Dr. Lisa Giombini: Too Good to be True. Plagiarism, Authenticity and the Arts

Duration: 45:25 min.

Filozofka umenia a estetička z Universita Roma Tre (Taliansko) - dr. Lisa Giombini, ktorá je momentálne na svojom výskumnom pobyte v Prešove (Inštitút estetiky a umeleckej kultúry, FF PU v Prešove) predniesla výsledky svojich výskumov populárnou formou (v anglickom jazyku) v stredu, 11. 12. 2019 o 11:00, v Galérii Caraffova väznica v Prešove. Dr. Giombini je významnou výskumníčkou v oblasti hudobnej ontológie, no v ostatnom období sa venuje najmä problematike filozofických aspektov reštaurovania a autenticity pamiatok po ničivých zásahoch prírodných katastrof. Je autorkou knihy Musical Ontology: a Guide for the Perplexed (Mimesis, 2017) a členkou niekoľkých európskych a svetových filozofických organizácií. V Prešove sa predstavila svojimi prezentáciami už pred rokom, na každoročnej konferencii, ktorú organizuje Inštitút estetiky a umeleckej kultúry na pôde Filozofickej Fakulty Prešovskej univerzity. Od októbra tohto roku je dynamickou a aktívnou súčasťou kolektívu inštitútu a už sa prezentovala na Philosophy Day Night v klube Wave, ako aj prostredníctvom workshopu Banal Tales pre študentov estetiky vo fakultných priestoroch.

V prešovskej Galérii v Caraffovej väznici sa predstavila prednáškou Too Good to be True. Plagiarism, Authenticity and the Arts (Príliš dobré na to, aby to bola pravda. Plagiátorstvo, autenticita a umenie). V odhaľovaní tejto fascinujúcej témy sa zaoberala otázkami nevyhnutnosti autenticity a originality vo svete estetiky umenia a spochybní negatívne vnímanie plagiátorstva. Naopak, poskytla pohľad, ktorým by sme mohli vnímať plagiátorstvo ako bežnú, normálnu umeleckú prax.

Too Good to be True

Plagiarism, Authenticity and the Arts

When she died of cancer in June 2006, English pianist Joyce Hatto was hailed as a musical genius by the press. In the previous thirty years, despite illness, she had proven capable of mastering an incredible repertoire, encompassing nearly the entire literature ever composed for piano. Prodigy of old age, she was thought to deserve a place of honour in the annals of classical music. Which, indeed, she obtained – as a plagiarist, though. Hatto’s fake recordings, all stolen from other interpreters, have given rise to one of the greatest scandals in music history.

But why do we oppose to plagiarism in the first place? The topic has been to the core of a long-standing philosophical debate, significantly started with Goodman’s discussion of authenticity in Chapter III of his Languages of Art (1968). Some theoreticians (Goodman 1968; Danto 1981; Sagoff 1978) have argued that the value our culture places on originality is justified, since authenticity is essential to an artwork’s identity and a prerequisite for it to have aesthetic significance. Other (Lessing 1965; Zemach 1989; Jaworski 2013) have retorted that the great store we set by originality is just fetishism, sentimentalism, or even plain snobbery. If we could ever get rid of these irrational presuppositions, we might come to accept plagiarism as a normal practice – we might, that is, enjoy Hatto’s recordings just like those of anyone else.

More than being just a matter of cultural or sentimental values, in this paper I argue that our interest in originality has to do with the idea of art itself as a special form of human accomplishment. One fundamental intuition in this regard is the assessment of the artwork as the result of a unique creative human act. Similarly, Dutton (1979, 2003, 2009) has contended that people assess all artworks as the end-point of human performances. From this perspective, art is like any sort of performing activity, including sport: we care how the obtained results have been achieved; if they have come out from natural vs artificial skill, for instance (Newman and Bloom, 2012). Unrevealed forgery and plagiarism trigger our admiration through a form of deception: they disguise the accomplishment. There might, however, be increasing confusion in the future over what counts as a fake. Given the advances in the field of audio-visual material digital alteration, is our view of artistic authenticity going to change?

Biography

LISA GIOMBINI is Junior Researcher at the University of Roma Tre (Italy), Department of Philosophy, Communication and Visual Arts and Visiting Research Fellow in Philosophy (2019-2022) within the School of Humanities at the University of Hertfordshire, UK. In 2015 she was awarded a PhD in Philosophy by the University of Lorraine (France) and the University of Roma Tre (Italy), with a focus on music ontology and meta-ontology. She was subsequently DAAD post-doctoral fellow at Stuttgart National Academy of Fine Arts (2016) and at the Institute of Philosophy of Freie Universität Berlin (2017/2018). In the Winter Semester 2019, she will be working at the Institute of Aesthetics and Art Culture of the University of Prešov, Slovakia, as a Research Grantee of the National Scholarship Programme of the Slovak Republic. She is the author of Musical Ontology: a Guide for the Perplexed (Mimesis, 2017) and a member of several philosophical association in Europe and abroad.